Articles

Interested in writing for us? Contact us below.

The Gamification of The Irish Famine.

Presley O’Bannon: The Irish American Who Fought the Barbary Pirates

Islamic incursions into Europe, during the late Ottoman era and into the early 1800s, are well documented in history. However, what is less know is how Irish America is tied to the American confrontation with the Barbary pirates, embodied by Irish American Presley O’Bannon. In today’s world, forgetting what our ancestors fought to defend comes at a cost. It dulls our ability to recognize similar patterns, and erodes the cultural foundation necessary to defend our homes.

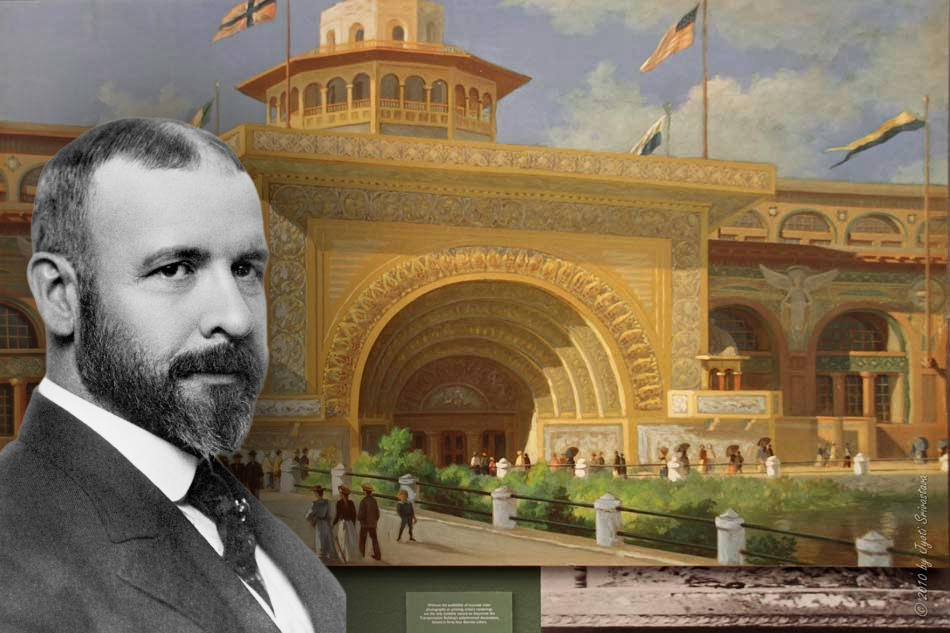

The Skyscraper: The Vision of Louis Sullivan, an Irish American

Boston, New York, Chicago… All cities with mesmerizing skyscrapers & architecture that would be hard to replicate in today’s world. The intricate ornamentation and towering buildings have inspired many across the globe, but many don’t know they have Irish America to thank for that inspiration.

Irish-America: A Journey from the Fenian Raids to NORAID

Irish nationalism, fueled by the tragedy of the Famine, found itself nurtured by emigrants in the prosperous industrial economy of the United States.

NRC’s Statement on Recent Political Violence

The Nationhood Revival Coalition condemns the recent wave of political violence. What we face is not protest, but a violent, organized ideology operating across borders with one aim: to silence nationalists. From Irish and American nationalists to countless others across the West, these leftist networks have singled us out for attack.

William James MacNeven: Rebel, Scientist, and Father of American Chemistry

William James MacNeven, a member of the United Irishmen Society, became one of the most prominent physicians in New York City in the early 19th century. Following the failed rebellion of 1798, MacNeven joined the French Army as a Surgeon-captain in the Irish Brigade, before arriving in the United States where he would earn recognition as the father of American Chemistry.

What is the Purpose of an Irish State?

Thereby, the purpose of the state is to provide the means for the ‘Irish’ to become ‘Gaels’.

The Final Days of Sinn Féin

In every movement that lives long enough to taste the air of power, there comes a time when it must look itself in the mirror—and not all who gaze back will like what they see.